Researching Sects and tribes in the Syrian conflict: Positionality and methodological challenges

8th Mar 2024 by Haian Dukhan

The Arab Spring protest movement has sparked hope for the emergence of a civic national identity capable of supplanting current authoritarian regimes. However, the outbreak of bloody civil wars has exposed underlying tensions, leading to the resurgence of subnational identities, including tribal and sectarian affiliations. These identities have always simmered below the surface, covertly exploited by authoritarian regimes as a strategy to divide and conquer.

First and foremost, it's crucial to acknowledge that within the field of 'sectarianism studies' in the Middle East, tribal communities have been significantly overlooked. The predominant focus on religious and political identities, particularly the divisions between major religious factions such as Sunni and Shia Muslims, tends to eclipse tribal identities and affiliations. These tribal affiliations often cross sectarian boundaries, adding layers of complexity that challenge the conventional sectarian narrative. Furthermore, the nation-building efforts in the Middle East have frequently aimed at diminishing or integrating tribal identities into a unified national identity. This endeavour, combined with the prevailing discourses on modernisation and development, has led some scholars to perceive tribal groups as remnants of a bygone, pre-modern era, rather than recognising them as dynamic and pertinent political entities. Consequently, tribes, particularly in urban areas, are often the targets of xenophobia. Moreover, there exists a propensity, both in the media and within certain academic circles, to distil intricate identities and political alliances into simplistic, palatable stories. Tribal communities, with their complex alliances and interests that often surpass sectarian divisions, do not easily conform to these reductive narratives. This misalignment underscores the need for a more nuanced understanding of the role and significance of tribal identities in the broader socio-political landscape of the Middle East.

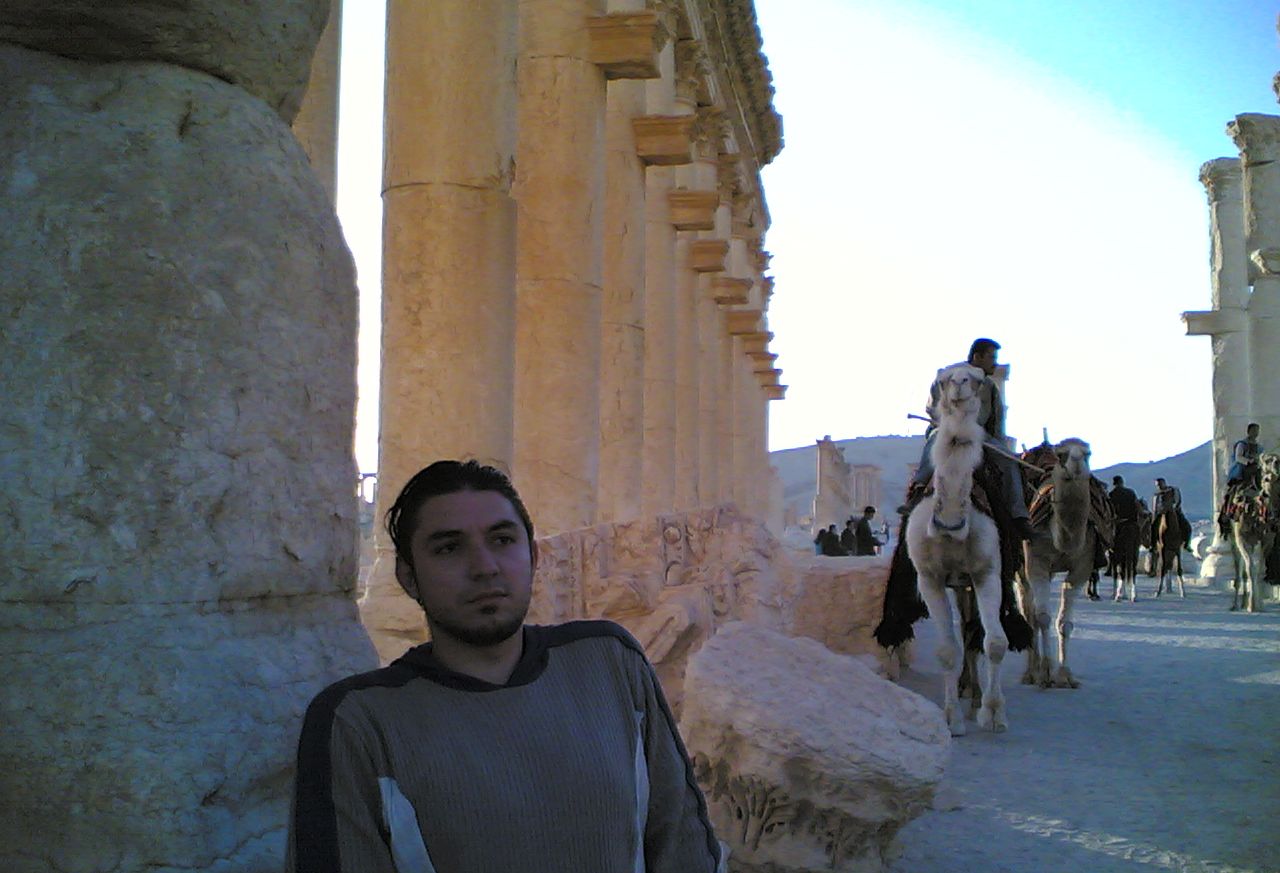

In 2012, I began exploring the resurgence of tribal and sectarian identities within the protest movement during the Syrian uprising. This brief reflection examines my initial forays and the methodological hurdles faced. The historical city of Palmyra, located centrally in Syria between Homs and Deir Ezzor, holds a significant place in my life story. Growing up amidst its ancient streets and rich cultural tapestry, I found myself deeply influenced by the ethos of my surroundings. In Palmyra, familial conversations often revolved around tribal affiliations and their role in shaping local dynamics, particularly during the Baath Party elections. These discussions provided me with a firsthand glimpse into the intricate interplay between identity, power, and opportunity within our community. Listening to my grandparents speak proudly of their tribal heritage, I became attuned to the nuances of our social landscape. The fervent competition among clans for representation in government circles underscored the significance of tribal affiliation in accessing resources and influence. Witnessing the impact of these dynamics firsthand, I began to recognise the profound ways in which societal structures shape individual lives and opportunities.

In Palmyra, where the majority of the population adhered to Sunni Islam, sectarian tensions simmered beneath the surface, exacerbated by the presence of a significant Alawite minority, many of whom held positions within the security services. Despite this demographic reality, public discourse on sectarianism remained a taboo subject, fraught with potential peril. I vividly recall an incident from my childhood when an innocent inquiry about the meaning of "Alawite" prompted a swift and stern response from my father. His visceral reaction, manifested in a slap across my face, spoke volumes about the gravity of discussing sectarian matters openly. In his eyes, such conversations posed a direct threat to our family's safety, as any hint of sectarian discord could potentially endanger his life and livelihood. This incident left an indelible mark on my consciousness, serving as a stark reminder of the delicate balance between curiosity and self-preservation in our socio-political reality.

Between 2003 and 2009, I worked in the field of International Development in Palmyra. During this period, I was part of a FAO project where I became familiar with the work of Professor Dawn Chatty, who worked as a consultant for the same project. Her research on the last of the fully nomadic Bedouin tribes in the Syrian Desert had a profound impact on me, igniting a desire to learn more about my ancestors' lost heritage. By the time I turned 28, my grandparents had passed away, and I hardly heard anything from my parents or other relatives about their Bedouin past.

In 2009, I was fortunate to receive the Chevening Scholarship to pursue a master's degree in International Development at the University of East Anglia. Despite my dissertation supervisor's warnings that I should not write any piece critical of the Syrian government's policies, I was determined to analyse the challenges faced by the nomadic Bedouin tribes around Palmyra. These challenges happened mainly as a result of the implementation of international development projects, especially the establishment of reserves to protect endangered animals and birds in the Syrian Desert.

Six months after finishing my MA and returning to Syria, the Syrian uprising erupted, plunging the nation into a vortex of unrest and upheaval. Amidst the chaos, I observed a resurgence of tribalism permeating the discourse of both the regime and the opposition. From the streets of Dar’a to the alleys of Palmyra, echoes of tribal solidarity and calls for tribal revenge reverberated across the Syrian landscape. It was a landscape marked by fragmented tribal components, manipulated and mobilized by competing factions in their quest for power. As I navigated through the tumultuous currents of the uprising, I couldn't help but notice the sectarian undercurrents that flowed beneath the surface. Conversations with Syrian friends in Palmyra revealed a spectrum of perspectives, ranging from accusations of the regime being a purely Alawite entity serving as a proxy for an Iranian Shiite axis to narratives of Sunni victimization at the hands of sectarian oppression. Amidst these conflicting narratives, I found myself grappling with fundamental questions about the nature of tribes and sects, and their significance within the Syrian conflict. How do these identities intersect with the broader socio-political landscape, and what role do they play in shaping the trajectory of the conflict? These questions gnawed at my consciousness, propelling me towards a deeper exploration of the intricate dynamics at play within Syria's complex tapestry of identity and conflict.

In 2012, I crafted a research proposal for my PhD, focusing on the study of tribalism within Syrian society. Thanks to the generous support of the Asfari Foundation, I was awarded a scholarship to pursue my doctoral studies at the University of St Andrews. Following the completion of my PhD, I became involved in another research project centered on conducting microstudies regarding the issue of sectarianism within the Syrian Civil War. This journey, marked by academic inquiry and fieldwork, has been instrumental in shaping my understanding of tribes and sects within the context of the Syrian conflict. Now, I will provide a short overview of some of the methodological challenges I encountered while conducting my research over the past decade.

When delving into the intricacies of researching tribes and sects within the Syrian conflict, I found myself grappling with three distinct narratives that emerged within the existing literature. These narratives presented not only challenges but also opportunities for understanding the complexities of identity dynamics within the Syrian context. Firstly, there was the pervasive denial narrative perpetuated by Syrian intellectuals hailing from both urban and rural backgrounds. Many of these intellectuals adamantly rejected the notion of tribal existence in Syria, attributing it to a sense of societal shame rooted in the belief that acknowledging tribal affiliations implied a failure to progress beyond a pre-modern stage. Some even dismissed tribes as mere constructs of Western colonial imagination. I vividly recall an encounter with a Syrian intellectual whose response to my inquiry about tribal structures in the region was stark: "My knowledge of tribes is like your knowledge of astronomy." This poignant retort underscored the glaring gaps in understanding within his own community.

Secondly, there existed the orientalist depiction of Syrian society as inherently divided along sectarian and tribal lines, with identities rigidly fixed and inherently prone to violent conflict. This perspective often advocated for the partitioning of the country along tribal and sectarian lines as a potential solution to the Syrian war. However, such essentialist views failed to capture the fluidity and complexity of identity dynamics on the ground.

Lastly, the instrumentalist narrative portrayed tribes and sects as mere instruments manipulated by both internal and external actors to serve their political and security agendas. While this perspective shed light on the instrumentalization of identity for strategic purposes, it overlooked the agency inherent within tribal and sectarian communities. The reality on the ground revealed that tribes and sects possess their own agency, often operating beyond the full control of political actors and challenging simplistic narratives of manipulation.

Navigating through these divergent narratives, I found myself confronted with the task of reconciling contradictory viewpoints and situating my own research within this complex landscape. This process underscored the need for a nuanced and contextual understanding of tribes and sects within the Syrian conflict, one that acknowledges their agency while also recognizing the multifaceted influences shaping their trajectories amidst the tumult of war.

Furthermore, there exists a noticeable dearth of anthropological or micro-studies conducted on the ground concerning tribes and sects in Syria. With few exceptions, such as Professor Dawn Chatty's micro-study on the al-Fadl tribe in the countryside of Damascus and the late Dr. Sulayman Khalaf's work on the al-Afadeleh tribe in Raqqa, there is a glaring absence of in-depth examinations detailing the lived experiences of researchers within Syrian tribal communities. This scarcity of research is even more pronounced concerning sects. The intellectual discourse surrounding sects in Syria often remains abstract, lacking a nuanced understanding of the realities on the ground. The authoritarian regime has erected formidable barriers, impeding researchers' access to communities in the periphery. Moreover, the onset of a brutal conflict has exacerbated the situation, posing extreme risks for researchers attempting to enter Syria and conduct fieldwork. As a result, the gap in micro-studies persists, hindering a comprehensive understanding of the intricate dynamics at play within Syrian tribes and sects.

Additionally, when delving into research on tribes and sects within the Syrian conflict, there exists a persistent risk of inadvertently favouring one narrative over others, particularly when access is restricted to certain groups. Given that the majority of Syrians displaced by the civil war belong to the Sunni Arab population, they often serve as the primary demographic for research interviews. However, this reliance on Sunni Arab Syrians may inadvertently introduce bias into the study. For instance, in my research on sectarianism in Deir Ezzor, I encountered challenges in connecting with the Shiite minority from the village of Hatla, which had suffered a massacre at the hands of Jabhat al-Nusra in 2014. The difficulty in accessing and engaging with marginalized communities such as this highlights the need for researchers to remain vigilant against unintentional biases and strive for inclusivity in their methodologies and narratives. This can be done by implementing a deliberate strategy to reach out to and include voices from a broad spectrum of communities, ensuring that the research methodology is explicitly designed to counteract demographic bias. Efforts should be made to establish trust and build relationships with minority communities, using local intermediaries when necessary to facilitate communication and understanding.

Finally, we must confront both a challenge and a crucial question as researchers: How can we ensure that our focus extends beyond the most prevalent narratives, which often overlook the experiences of women, activists, and internally displaced individuals? In reflecting on my study of tribal militias in Iraq during the conflict against ISIS, I encountered the remarkable story of Omaya Jbara, a courageous woman from the al-Jabbour tribe. Omaya not only rallied her tribe against ISIS but also actively participated in combat. Yet, many narratives surrounding tribes and sects fail to acknowledge the significant contributions of women like her. As researchers, it is incumbent upon us to actively seek out and amplify the voices and experiences of marginalized groups, ensuring that our work remains inclusive and representative of the diverse realities within conflict zones.

In conclusion, the journey of researching tribes and sects within the Syrian conflict underscores the intricate interplay between identity, power, and conflict. From confronting prevailing narratives to grappling with methodological challenges, this academic pursuit has illuminated the multifaceted nature of societal dynamics in Syria. As researchers, it is imperative to remain vigilant against biases and to strive for inclusivity in our methodologies and narratives. By amplifying the voices of marginalised communities and embracing diversity, we can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities shaping the Syrian landscape, ultimately working towards a future marked by justice, understanding, and reconciliation. My insights, grounded in my upbringing and experiences in Palmyra, critically inform and shape my analysis, providing a unique lens through which the intricacies of Syria's conflict are explored and understood.