Critical Approaches to State and Sovereignty: Part 2 (Delatolla)

4th Dec 2023 by Simon Mabon

Colonialism and the State

Andrew Delatolla, University of Leeds

The modern state as a concept is elusive; just when you think you have some formulation, some definition, or some working theoretical grounding, the rug is pulled out from under you. My own journey in trying to ‘deal’ with – or make sense of – the state began with the teachings of the late Kym Pruesse, an activist, artist, and professor at OCAD in Toronto. It was the first time I was encouraged to think about how the state seeks to preserve the politics of respectability, in society and the halls of state institutions. Here, it is possible to cite Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (2019), an important rumination on the state’s tools and practices for maintaining civilité (1985). In doing so, it is evident how the violence of the colonial state ‘boomeranged’ back to the metropoles to give way to the modern Western state. Importantly, however, the colony as testing ground continues to differentiate the colonial state from the modern Western state. The colonies, including contemporary colonial configurations such as Israel’s occupation of Palestine, and Spanish Ceuta and Melilla, were and continue to be testing sites for new methods and means of population control, that then become policy, sold to the masses as progress and civilization, in the modern state. Notably, another distinction is that colonial powers do not govern native populations with the aim to ensure that they represent the colonial nation’s benchmark of civilisation. Instead, these native populations are in service to the colonial power and their lives are not respected as they may be in the metropolitan citizens. Within these colonial configurations where colonised populations are treated differently, examples include the divergence in treatment between indigenous populations around the world, including the USA, Canada, Australia and South Africa (Yao and Delatolla, 2021), Palestinians and Israelis, with the latter example being subjected to heightened forms of militarized policing, extrajudicial killing, and surveillance by the Israeli state and its institutions (Puar, 2017).

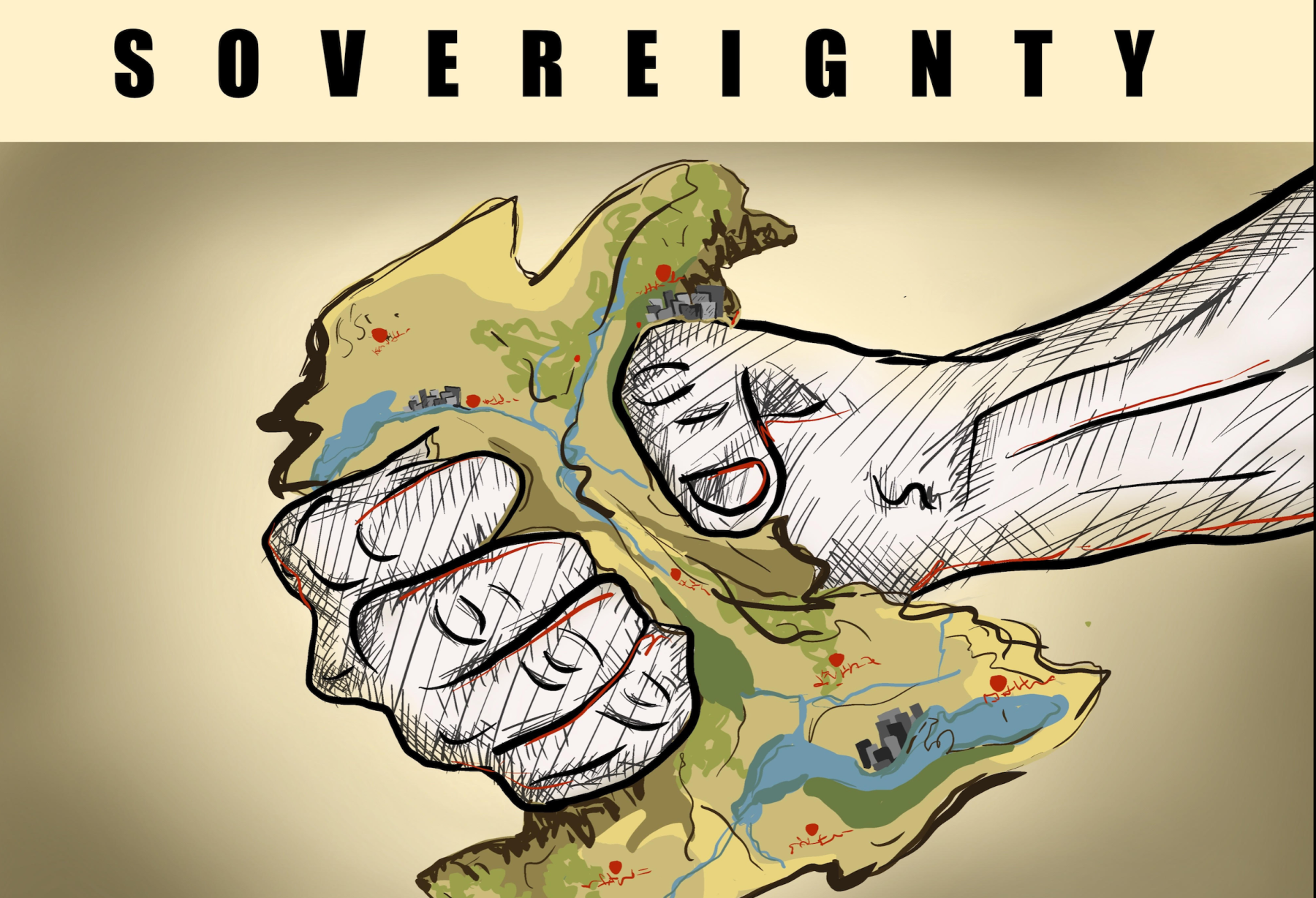

When viewed through this vector, the state is a container to assert control over its population. This does not veer too far from Weber’s checklist of what a state is: a territory, a monopoly of (legitimate) force, a government, and a population (2004). However, the state, even with its most legitimate and democratic institutions and structures applies different forms of violence to assert control, to ensure civilité, and to enable the comfortable maintenance of the bourgeoisie. Delving into these dynamics, Foucault’s Discipline and Punish can be pushed further: the state can also be understood as a killing machine. Its creation in the Middle East and North Africa centred on creating containers to enable extraction and exploitation for the benefit of European metropoles, justified by racist notions of civilizational hierarchies (Delatolla).

These arguments can also interact and build on Agamben’s ideas outlined in the State of Exception and, relatedly, Mbembe’s arguments on colonialism and the postcolony (2005). Where Agamben argues that exceptions to standard practices of governance exist – often directed onto undesirable bodies, as was the case with the so called ‘War on Terror’, Mbembe argues that the state of exception was used to justify violence and killing against people who, in one way or another, are not valued as people but are reducible to their utility.

If we are to understand the foundations of the modern state in the Middle East and North Africa as being the result of colonial institution building and governance, then it makes sense that the institutions and structures of the post-independence ’post-colonial’ state reflect the forms of extraction and violence of the previous era; despite decades of revolutions, coup d’états, and international attempts at contemporary development and statebuilding. By examining the post-colonial state through this lens, two questions emerge: 1) why this is the case and 2) how have these institutions and structures of the colonial state system remained? The answer to these questions can be found in the political continuities of the international system which offers an overarching structure that is maintained by the trans-historical interests of the most powerful states. Although much scholarship, historical and political, temporally divides political history into different eras, producing discursive and intellectual ruptures that, in turn, reflect the theoretical frameworks used to explain historical and political phenomenon, it is, I argue, unhelpful in trying to answer questions concerning statehood. As such, when answering the above questions, we need to understand how institutions and structures were built on and from colonial policies and practices of scorched earth; transforming societies to fulfil an economic and political purpose that benefitted those wielding violence; including foreign colonisers and local native elites that worked closely with oppressive forces.

By understanding the post-colonial state as being tethered to the colonial state, despite declarations of independence and subsequent political upheavals and transformations in many of these states, it becomes evident that the institutions and structures that were crucial to colonial governance were never destroyed. Instead, practices of colonial governance and colonial institutions were often seen by new leaders as necessary to retain power and control by the incoming political elites. Here, the international system and states at the helm of maintaining the system can be viewed as kingmakers, more concerned with the status quo than providing space for a new political project. Indeed, there are many instances where key international players have allowed new elites to fall, and – at times – actively enabled their fall in fear of disruptive and novel political projects. From this argument, the example of Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh in Iran and, more recently, the international silence regarding the President Al-Sisi’s coup against President Mohamed Morsi, can be understood.

By viewing the post-colonial state as embedded and tethered to colonial histories, consistently enmeshed in an international system of interests that, arguably, have not changed much since the late nineteenth century, it is possible to highlight key continuities that expose an ongoing form of colonial violence. When examining the case of Egypt, for example, a state that had experienced European colonialism and empire with the French occupation from 1798-1801 and the British occupation from 1882 under a veiled protectorate, it is possible to understand the impact of European colonialism and empire by looking at physical space, as Timothy Mitchell (1991) does, the military, and the law. While under the legal and political purview of the Ottoman Empire, the Othman Penal Code of 1858 was applied in Egypt. The Othman Penal Code of 1858 had been influenced by the French Code of 1810 and by the French Penal Code of 1837. Subsequently, Lord Kitchener, a British Colonial Administrator, ordered a review of the Egyptian 1909 Penal Code, leading to the Draft Penal Code of 1919, being passed in Parliament in 1937. Although the code has been since amended, much of the language and structure remains in place (Human Rights Watch, 2004). These laws frame governmentality, providing the scope of the government to discipline and punish citizens in a manner that better reflects the positionalities of French, and later, British ideas of civilité, or civilized behaviour.

French and British influence on the legal parameters of the development of the modern and modernising Egyptian state reflected European desires to instil civilized behaviour. This occurred with the addition of racial-biological determinism that placed Egyptians and Egyptian society in a lower hierarchical place in relation to the French and British; requiring systems of governance that necessitated strength over leniency to create the moral, civilized, and modern society required for independence. Part of this notion of civilité that was embedded in colonial governance was a form of heterocolonialism that gave way to new, restrictive, and heteronormative forms of sexual governance (Delatolla, 2021). The degradation and subsequent elimination of perceived non-masculine behaviours and same-sex relations was bound up in European ideas of civilized engagement that were supported through increased medical and legal developments. In Egypt, this included the elimination of the khawal, a male dancer dressed in feminine attire. This is not to say that conservative attitudes, particularly among rural and religious communities, did not exist and were not opposed to such social practices. Instead, it is to highlight the expressions, categories, and framings used today are distinctly modern, often originating in Europe. [1]

Nevertheless, with the social, political, and subsequently legal enforcement that can be characterised as heterocoloniality, a form of violence was enacted and embedded into the state; requiring the elimination of non-heteronormative performances and acts. Central to this form of heterocoloniality, the state’s relationship to sex and sexuality existed relative to biological constructions of gender that stripped women of their right to be political and economic agents. This was evident in Egypt, as in other former colonies, including Algeria, Lebanon, and Syria. In Algeria, pre-independence, French colonisation has been attributed to the decimation of women’s engagement in economic activities, including traditional handicraft. During the struggles for independence, women were required to fight for national independence but not make political demands regarding their place within an independent nation-state. [2] For many, including women and those that did not fit within a colonial heteronormative framing of civilized engagement, the colonial state and the independent modern state, has continuously sought a politics of civilization and respectability to do with citizenship based on ideas of masculinity and hetero-social reproduction.

Following the Free Officer coup d’état in 1952 Egypt, a penal code based on anti-colonial principles was enacted. While valiant in its attempt to strip out the vestiges of British and French influence, the state, its institutions – including its army, and its law remained embedded in a hetero-colonial system. That is not to say that there was not a re-imagining of politics, but that the anti-colonial politics that were developing in this moment relied on a colonial framing of statehood. Unlike the establishment of colonial institutions and structures, the anti-colonial movement did not enact a policy of scorched earth. While propositions of a new political formations were developed in anti-colonial movements, the foundations of the colonial state, including the military and law, remained.

Despite the state gained its independence, its patriarchal and heteronormative structures of colonial governance remained intact. Although the state is not solely the result of patriarchy and heteronormativity, it is through this lens that makes visible the ‘state of exception’ enacted on particular communities under laws concerned with debauchery and immorality. Furthermore, it is through these legal articles that, the creation of the state of exception, that violence and, indeed, killing occurs.

Indeed, it is helpful to view the state as a container, but then the question that requires answering is: a container for what purpose? And, more importantly, for who? The purpose of the state is, arguably to organise populations into productive roles in capitalist systems and take on the responsibility to protect those populations from threats of violence and harm. Although this appears as a sound trade-off, when questioning who this trade-off is for, we can better understand the limited application of the state as a form of safety and security. In turn, statehood becomes a source of violence and death that cannot be unseen when examined through the spectre of a politics of respectability, civilité, and belonging – bringing to the fore a harsh reality of constant state of exception that not only seeks to discipline and punish, but eliminate.

References

Agamben, Giorgio, 2005. State of Exception, Chicago: University of Chicago Press;

Bauman, Zygmunt, 1985, ‘On the Origins of Civilisation: A Historical Note’, Theory, Culture & Society, 2(3), pp. 7–14.

Delatolla, Andrew, Civilization and the Making of the State in Lebanon and Syria. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Delatolla,Andrew, 2021, Homocolonialism: Sexual Governance, Gender, Race and the Nation-State, E-IR, https://www.e-ir.info/pdf/92079

Foucault, Michel, 2019, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin Books.

Laws Affecting Male Homosexual Conduct in Egypt’, Human Rights Watch, March 2004, https://www.hrw.org/reports/2004/egypt0304/9.htm

Mbembe, Achille 2001, On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Mitchell, Timothy, 1991, Colonising Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Puar, Jasbir, 2017, The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Durham: Duke University Press.

Weber, Max 2004, The Vocation Lectures. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

Yao, Joanne and Andrew Delatolla, 2021, Race and Historical International Relations. In: de Carvalho, B, Costa Lopez, J and Leira, H, (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Historical International Relations. New York: Routledge

[1] While Joseph Massad makes a similar argument, I have argued and continue to argue that the concern is not with modern categories of the homosexual or the LGBTQ+ but with the foundational category of heterosexuality and the heterosexual as a point of departure for thinking about other sexualities and sexual orientations. As such, it is not the ‘gay international’ the imposes a colonial ordering, but the ‘straight international’ that needs to be abolished.

[2] See the volume edited by Margaret Meriwether and Judith Tucker, 2019, A Social History of Women and Gender in the Modern Middle East. Taylor and Francis.